Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region

Mengi Li / 2019

Yale School of Architecture

The disappearance of 1.5 Million people of Muslim ethnic background in Western China has received shockingly little international attention and push back until very recently. Uyghur people have been rapidly imprisoned in secret in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) since 2016 in various so-called "re-education camps". China is reinforcing its power through the production of culture and identity, made possible by incredible amounts of construction development and architecture. This strategic and carefully coordinated campaign succeeds through its ability to blur physical and spatial boundaries, crossing domestic and international boundaries as well as a sense of temporality, spanning from the 18th century to 2019. This visual analysis seeks to bring together various dimensions- both physical and ephemeral- to allow for greater comprehension and discussion of this issue.

A Human Rights Crisis

The treatment of the Uyghur people in the Xinjian Region is arguably the most extensive internment campaign since World War II. Michael Kozak , the head of the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, in an apparent reference to the policies of Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union, stated that people “haven’t seen things like this since the 1930s,” and called the internment of more than a million Uyghurs “one of the most serious human rights violations in the world today.”

Citing credible reports, U.S. lawmakers at the head of the bipartisan Congressional-Executive Commission on China recently called the situation in the XUAR “the largest mass incarceration of a minority population in the world today.” (RFA Uyghur Service 2019)

![]()

Life as Uyghurs

Imagine that this is your daily life: While on your way to work or on an errand, every 100 meters you pass a police blockhouse. Video cameras on street corners and lamp posts recognize your face and track your movements. At multiple checkpoints, police officers scan your ID card, your irises, and the contents of your phone. At the supermarket or the bank, you are scanned again, your bags are X-rayed and an officer runs a wand over your body - at least if you are from the wrong ethnic group. Members of the main group are usually waived through.

You have had to complete a survey about your ethnicity, your religious practices and your “cultural level”; about whether you have a passport, relatives or acquaintances abroad, and whether you know anyone who has ever been arrested or is a member of what the state calls a “special population.”

This personal information, along with your biometric data, resides in a database tied to your ID number. The system crunches all of this into a composite score that ranks you as “safe,” “normal,” or “unsafe.” Based on those categories, you may or may not be allowed to visit a museum, pass through certain neighborhoods, go to the mall, check into a hotel, rent an apartment, apply for a job, or buy a train ticket. Or you may be detained to undergo re-education, like many thousands of others.

This is life in northwestern China today if you are Uyghur. (Millward 2017)

![]()

Displacement Through Development

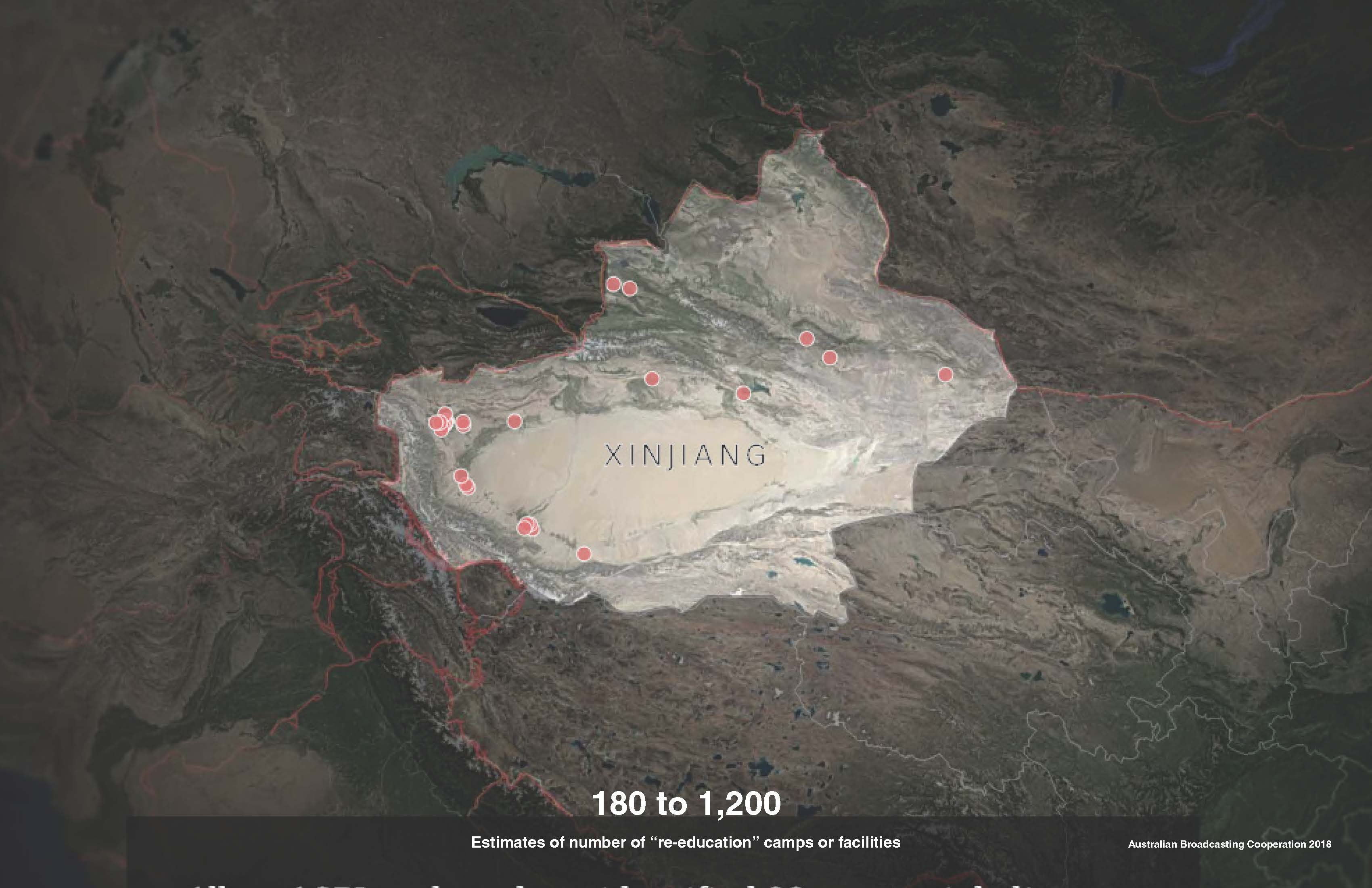

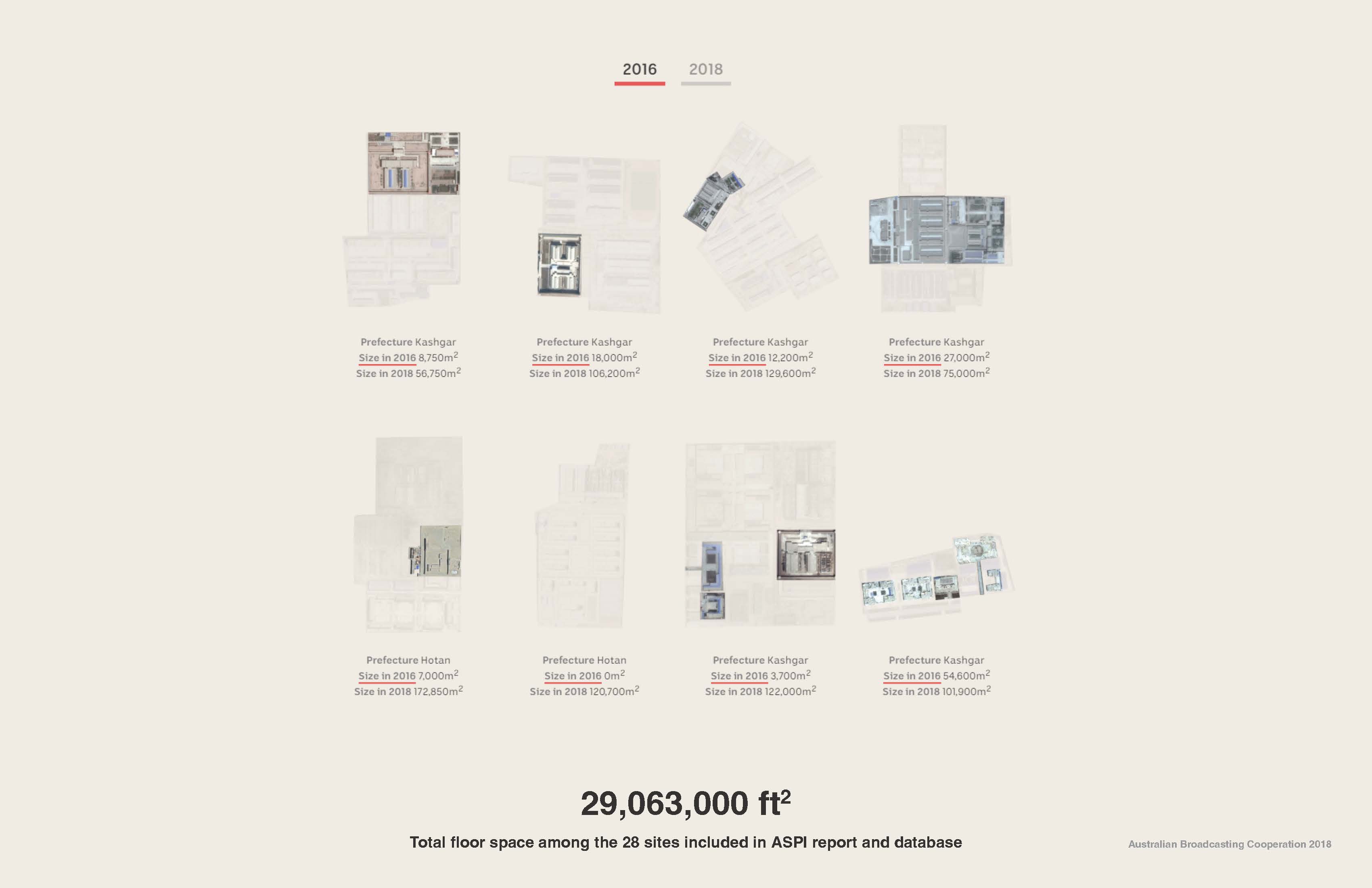

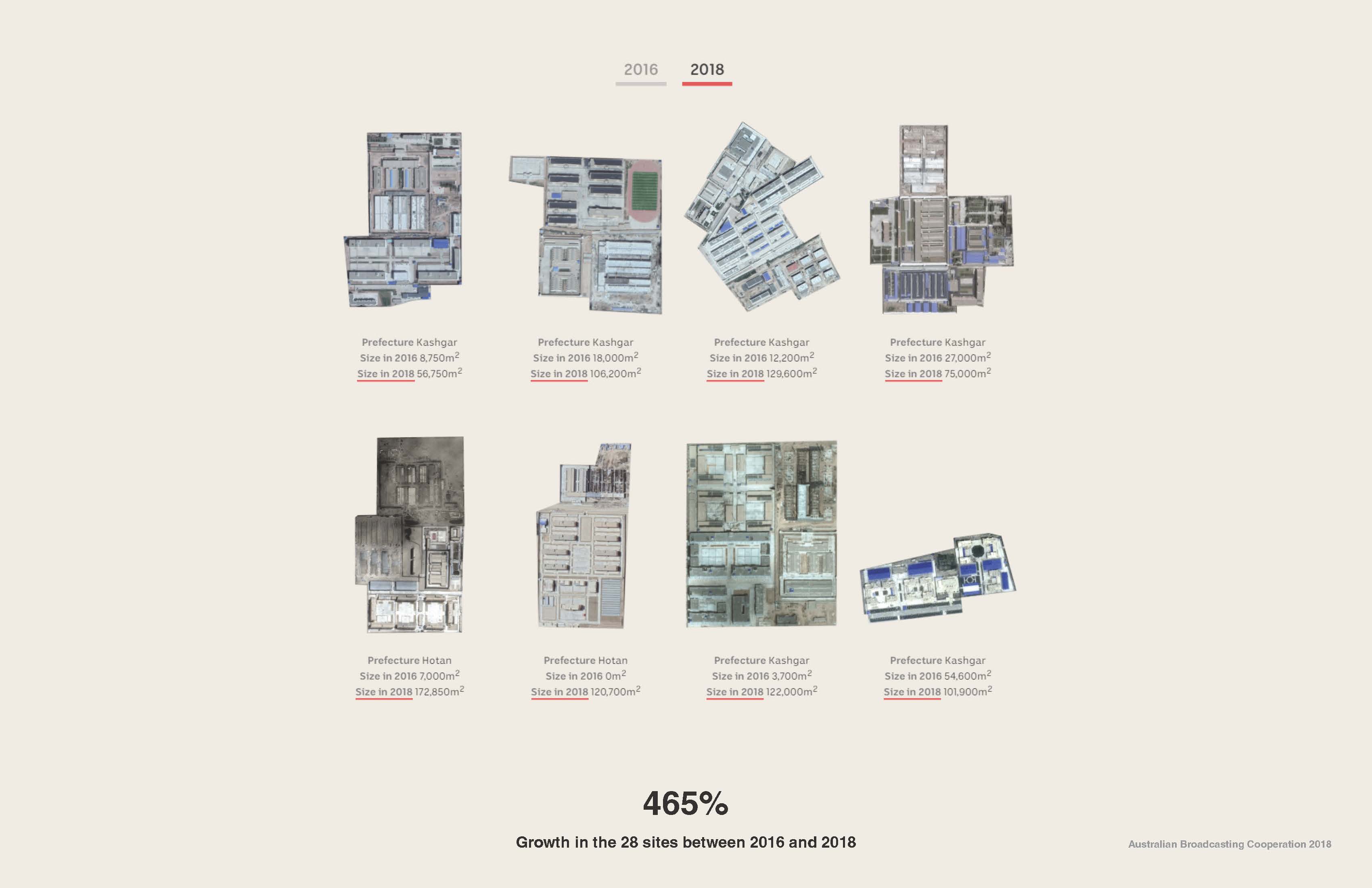

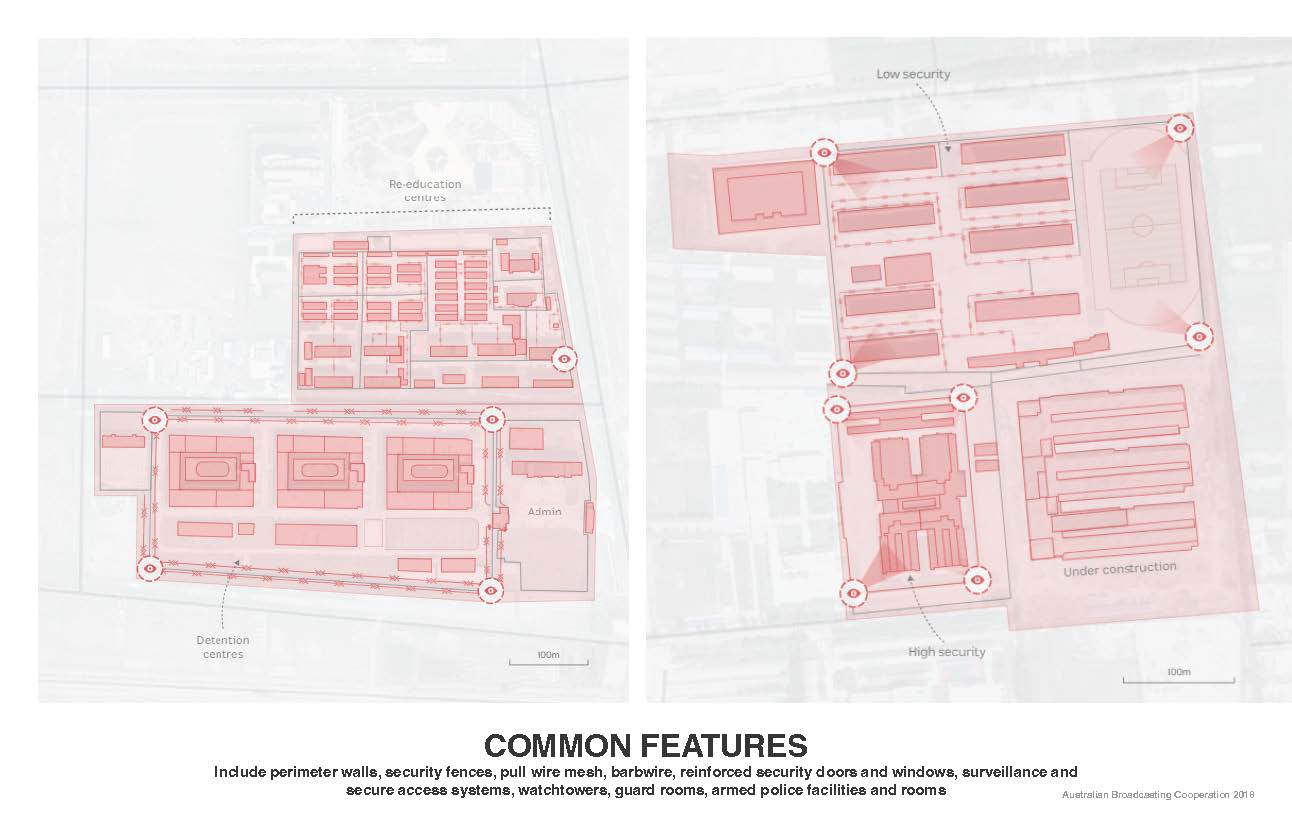

In the past decade alone, five new cities have been constructed as locations for the state to place the Uyghur people. These “cities,” comprised of re-education centers and detention centers, have grown rapidly in a span of just two years, and share many common features, including: perimeter walls, security fences, pull wire mesh, barbed wire, reinforced security doors and windows, surveillance and secure access systems, watch towers, guard rooms, and armed police facilities.

![]()

![]()

![]()

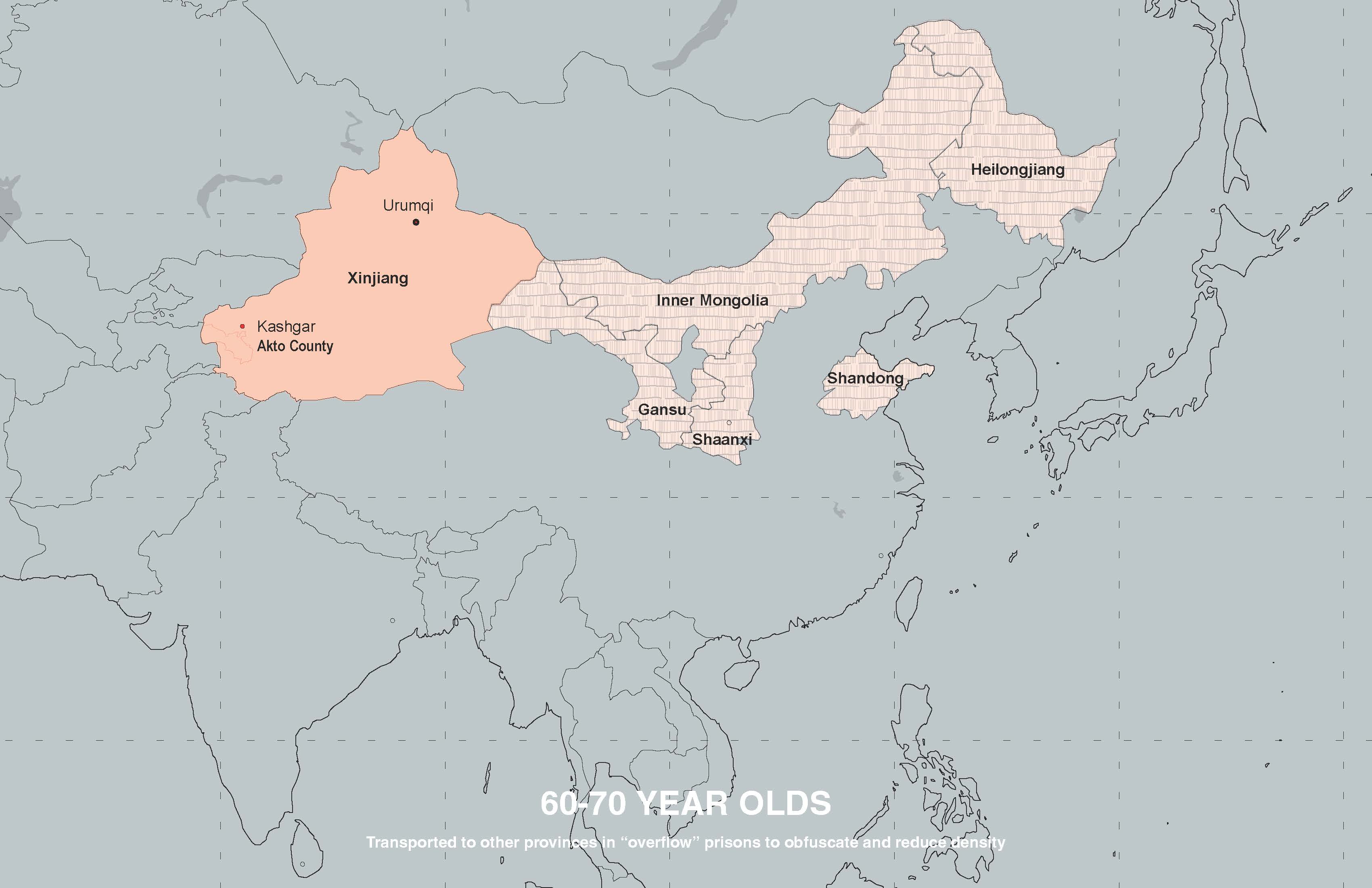

In order to reduce density, and to obfuscate the activities taking place in the re-education centers, older members of the Uyguhr population, mostly 60-70 year olds, are transported to “overflow” prisons in other provinces throughout the country.

![]()

China: The Global Capital of Surveillance

The state’s actions to detain and surveil members of the Uyghur population within the country itself has far-reaching implications beyond its borders. Eighteen countries on four continents are currently using Chinese-made intelligence monitoring systems, while thirty-six countries have been trained in the technology.

Using Ecuador as an example, by February 2011, with guarantees of state funding from Chinese diplomats, the country signed a deal with no public bidding process. Ecuador got a Chinese-designed surveillance system financed by Chinese loans. In exchange, Ecuador provided one of its main exports - oil. The money for the cameras and computing flowed straight to C.E.I.E.C. and Huawei, two Chinese tech companies with close ties to state power.

It became a pattern. In exchange for credit facilities that totaled more than $19 billion, Ecuador signed away large portions of its oil reserves. A surge of Chinese-built infrastructure projects, including hydroelectric dams and refineries, followed (Ibid.).

![]()

According to James Millward, who has written extensively on the subject, Beijing’s ambitions go much further than the abilities that those eighteen countries bought into. Today, the police across China gather material from tens of millions of cameras, and billions of records of travel, internet use, and business activities to keep tabs on citizens. The national watchlist of would-be criminals and potential political agitators in China includes 20 to 30 million people - more than Ecuador’s entire population of just 16 million. (Millward 2017)

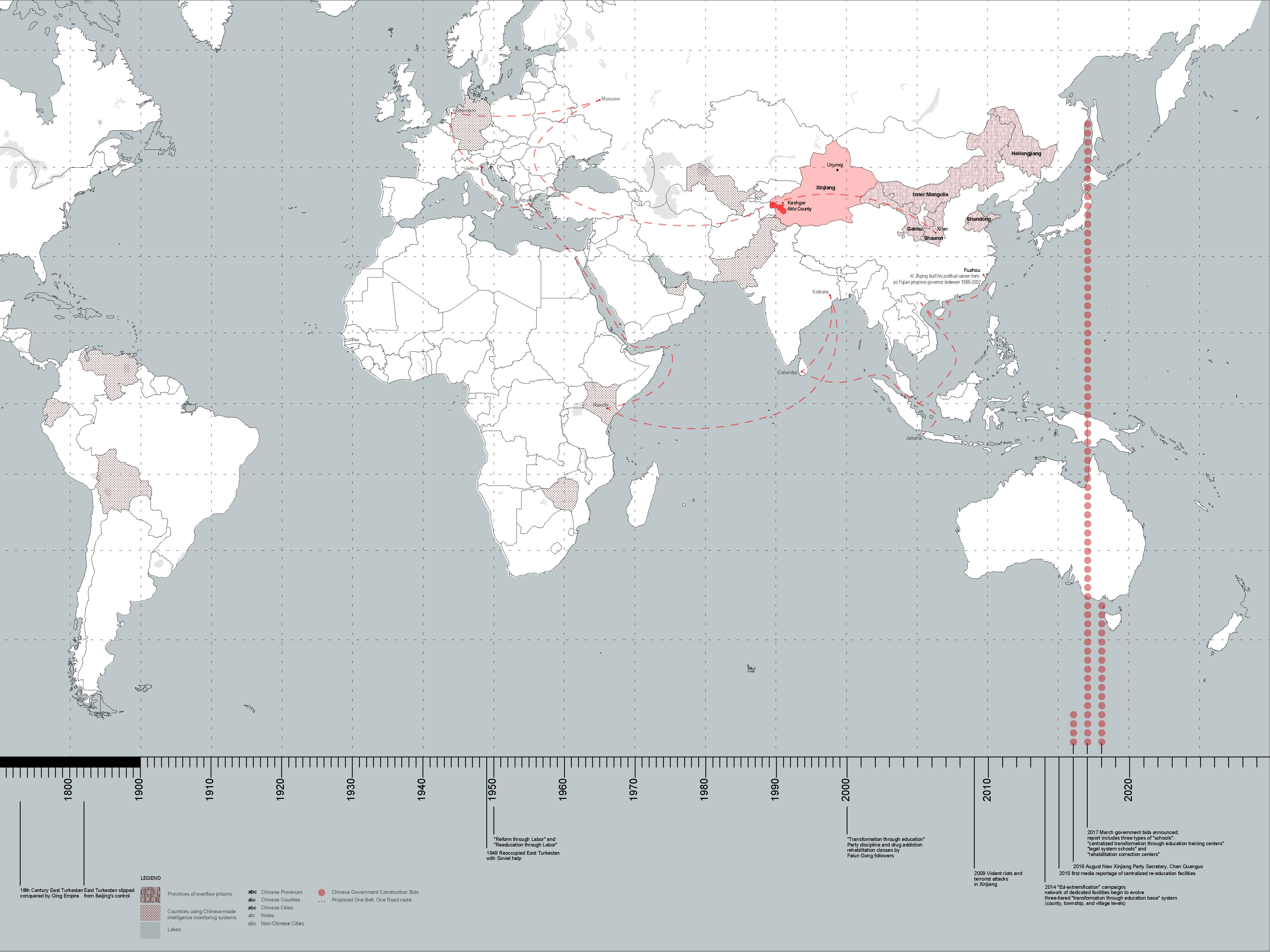

The map below is a composite drawing that shows the the extent of China’s reach today, from overflow detention centers and surveillance states around the globe, to a recent skyrocketing in government construction bids. At the scale of the territory, the mechanisms of logistics are able to be manipulated and monetized.

![]()

Yale School of Architecture

The disappearance of 1.5 Million people of Muslim ethnic background in Western China has received shockingly little international attention and push back until very recently. Uyghur people have been rapidly imprisoned in secret in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) since 2016 in various so-called "re-education camps". China is reinforcing its power through the production of culture and identity, made possible by incredible amounts of construction development and architecture. This strategic and carefully coordinated campaign succeeds through its ability to blur physical and spatial boundaries, crossing domestic and international boundaries as well as a sense of temporality, spanning from the 18th century to 2019. This visual analysis seeks to bring together various dimensions- both physical and ephemeral- to allow for greater comprehension and discussion of this issue.

A Human Rights Crisis

The treatment of the Uyghur people in the Xinjian Region is arguably the most extensive internment campaign since World War II. Michael Kozak , the head of the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, in an apparent reference to the policies of Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union, stated that people “haven’t seen things like this since the 1930s,” and called the internment of more than a million Uyghurs “one of the most serious human rights violations in the world today.”

Citing credible reports, U.S. lawmakers at the head of the bipartisan Congressional-Executive Commission on China recently called the situation in the XUAR “the largest mass incarceration of a minority population in the world today.” (RFA Uyghur Service 2019)

Life as Uyghurs

Imagine that this is your daily life: While on your way to work or on an errand, every 100 meters you pass a police blockhouse. Video cameras on street corners and lamp posts recognize your face and track your movements. At multiple checkpoints, police officers scan your ID card, your irises, and the contents of your phone. At the supermarket or the bank, you are scanned again, your bags are X-rayed and an officer runs a wand over your body - at least if you are from the wrong ethnic group. Members of the main group are usually waived through.

You have had to complete a survey about your ethnicity, your religious practices and your “cultural level”; about whether you have a passport, relatives or acquaintances abroad, and whether you know anyone who has ever been arrested or is a member of what the state calls a “special population.”

This personal information, along with your biometric data, resides in a database tied to your ID number. The system crunches all of this into a composite score that ranks you as “safe,” “normal,” or “unsafe.” Based on those categories, you may or may not be allowed to visit a museum, pass through certain neighborhoods, go to the mall, check into a hotel, rent an apartment, apply for a job, or buy a train ticket. Or you may be detained to undergo re-education, like many thousands of others.

This is life in northwestern China today if you are Uyghur. (Millward 2017)

Displacement Through Development

In the past decade alone, five new cities have been constructed as locations for the state to place the Uyghur people. These “cities,” comprised of re-education centers and detention centers, have grown rapidly in a span of just two years, and share many common features, including: perimeter walls, security fences, pull wire mesh, barbed wire, reinforced security doors and windows, surveillance and secure access systems, watch towers, guard rooms, and armed police facilities.

In order to reduce density, and to obfuscate the activities taking place in the re-education centers, older members of the Uyguhr population, mostly 60-70 year olds, are transported to “overflow” prisons in other provinces throughout the country.

China: The Global Capital of Surveillance

The state’s actions to detain and surveil members of the Uyghur population within the country itself has far-reaching implications beyond its borders. Eighteen countries on four continents are currently using Chinese-made intelligence monitoring systems, while thirty-six countries have been trained in the technology.

Using Ecuador as an example, by February 2011, with guarantees of state funding from Chinese diplomats, the country signed a deal with no public bidding process. Ecuador got a Chinese-designed surveillance system financed by Chinese loans. In exchange, Ecuador provided one of its main exports - oil. The money for the cameras and computing flowed straight to C.E.I.E.C. and Huawei, two Chinese tech companies with close ties to state power.

It became a pattern. In exchange for credit facilities that totaled more than $19 billion, Ecuador signed away large portions of its oil reserves. A surge of Chinese-built infrastructure projects, including hydroelectric dams and refineries, followed (Ibid.).

According to James Millward, who has written extensively on the subject, Beijing’s ambitions go much further than the abilities that those eighteen countries bought into. Today, the police across China gather material from tens of millions of cameras, and billions of records of travel, internet use, and business activities to keep tabs on citizens. The national watchlist of would-be criminals and potential political agitators in China includes 20 to 30 million people - more than Ecuador’s entire population of just 16 million. (Millward 2017)

The map below is a composite drawing that shows the the extent of China’s reach today, from overflow detention centers and surveillance states around the globe, to a recent skyrocketing in government construction bids. At the scale of the territory, the mechanisms of logistics are able to be manipulated and monetized.