Identity Verification

Valeria Flores / 2018

Yale School of Architecture

On a daily basis we seem to lose track of how many times we have to prove who we are to others in order to define how we move through space to carry out our many chores. Our identity defines our spatial realm without us even realizing it, or maybe we have grown so accustomed to verifying who we are that we don’t register the series of boundaries we cross hour by hour in an abstract way. Here is where my interest sprung for this investigation, where I intend to analyze the impact of Big Data on our real life and online identities. Some of the questions this paper seeks to answer are those related to the history and need for an identity and how through time there has been an intensification to have to prove who we are to have access to many of the services we require from day to day. More importantly, the paper includes a number of case studies of companies who have taken over the responsibility of assuring the veracity of their customers’ identities through data decentralization and material development as a form of biometrics. The fissures in the process of identification are what that draw our attention to how anxious our lives in the digital age have become in an ever growing neurotic quest to build a level of trust around who we are. At the same time, they become the gateways that compromise the security of how we interact with others’ identities.

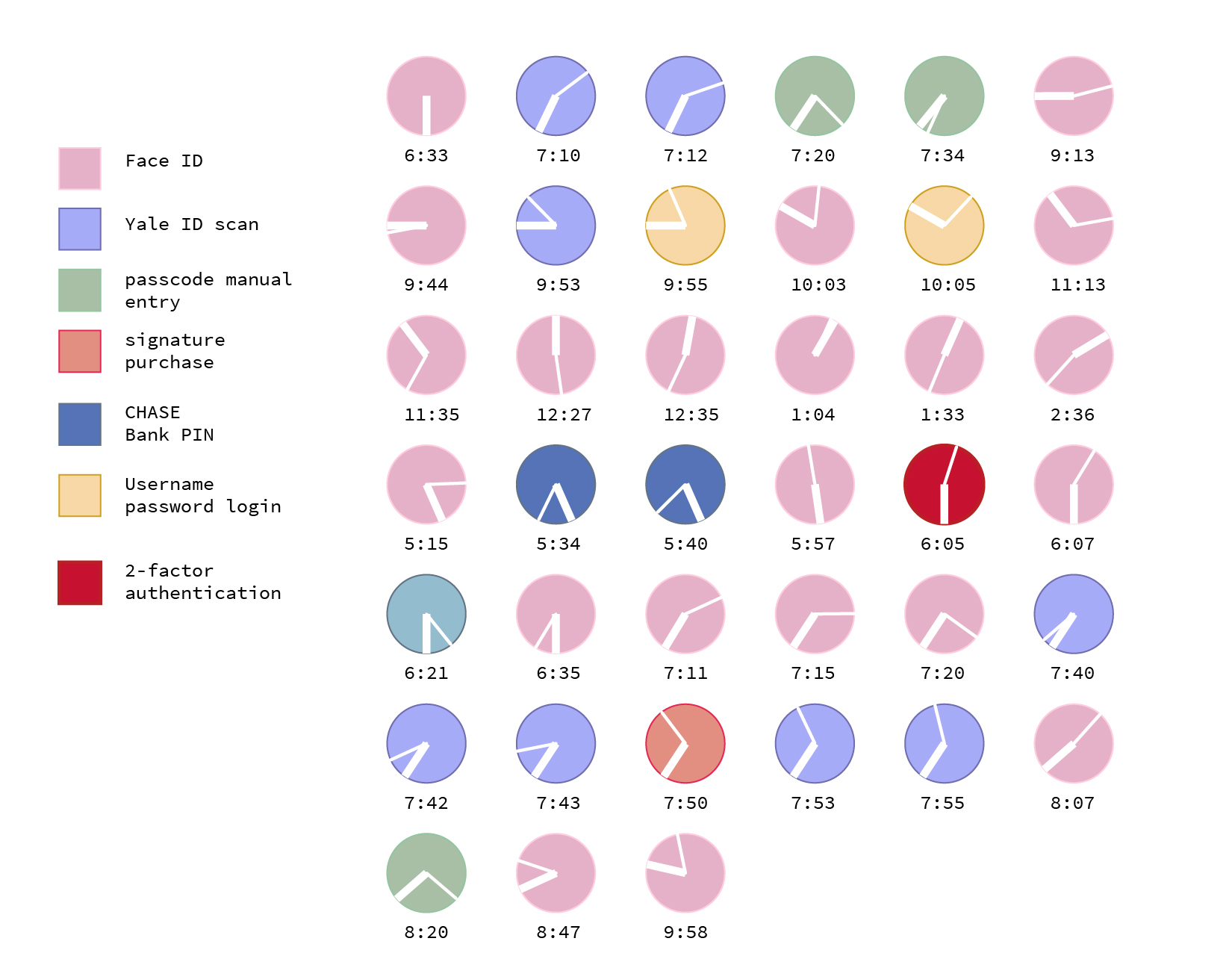

As a preliminary exercise to the written version of this investigation, I underwent an identity use analysis on a common work day for me. The following is a graphic showing how many times throughout the day I had to make use of identity validation systems to carry forward basic, routine chores as a student at the Yale School of Architecture.

![]()

![]()

These illustrations bring to light how ubiquitous it is for us to verify our identities on almost an hourly basis. Each and every single one of these annotations is an abstraction of the traces left as a recognizable individual in a determined space and time. What they become are symbols for “Individual X was at Y at time Z and made use of the service A/ purchased item B, etc”. Our physicality is transformed into data that can be easily compiled and traced. In the era of Big Data and constant surveillance this becomes a resourceful pool of information for governments, where they don’t really have to make an effort to control their population in motion, we on our own provide them with this information.

They can also be thought of as a series of barriers that we are constantly crossing in order to get on with our lives and have access to the services we have grown used to. Another interpretation for which this type of graphic can be used for is to shed a light on our interaction or more even, dependency on our smartphones. When we put into numbers how many times we interact with our phones, it is eye-opening to see how much information about ourselves we’re currently feeding into these devices. This graphic record was carried out on a day after finals, where the turmoil of moving around the Architecture building was significantly less than usual and reflects on a lower use of login interfaces.

Personally, one of the most prominent discoveries for me was how Face ID has increased the ease of interaction with my phone, to the point where I find myself checking it more times than usual. The downside of this? I’m feeding more and more information about my facial characteristics to a device that can eventually improve its accuracy for facial recognition technologies used by corporations and governments. Overall, it would be interesting to carry forward this record over a week and represent it almost like a map with the locations of each of these identity interactions pinpointed to see how our identity allows us to move through space.

The concept of identity is already a slippery one without even taking Big Data into consideration. When we reflect upon how we even conceive the idea of identity, we realize that from the youngest of ages we always understand our identity as a game of representation and interpretation. Recognizing ourselves in the mirror is an interpretation of how we are represented by a reflective surface. There is no direct, empirical access to what our identity is, it is always conditioned through the medium of its representation: a photograph, a mirror, a passport, etc. Given the difficulty in defining identity truthfully, it is understandable why this becomes such a key element to our everyday lives. What does identity do for us? Why are we so concerned with guaranteeing its veracity and why do we have this constant need of distinguishing ourselves apart and then having to prove who we are to others?

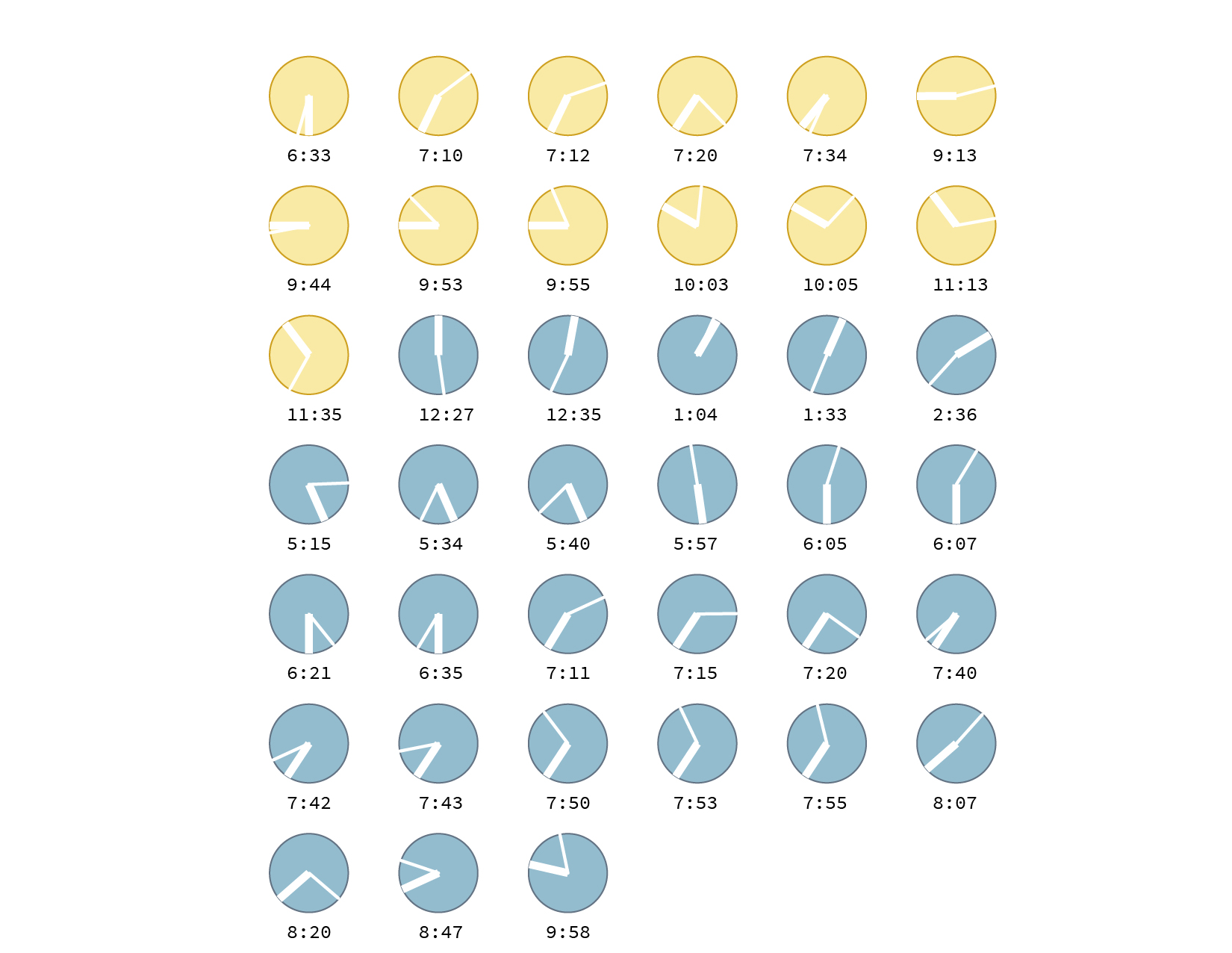

In order to address these questions, it becomes necessary to first understand how we have recorded our individuality through time. The history of identity provides us with an understanding of how the degree of neuroticism regarding who we are has evolved throughout time. More importantly, this graphic timeline shows the growing technologies that spring out of the need of more layers of veracity added to the representation of who we are to others. [1]

![]()

First off, our identity exists within a paradox of freedom and control. Identity both provides us with the freedom to define who we are and how we want to be seen by others whilst simultaneously being a form of power and control for governments. Consequently, our identity establishes a trace that

connects who we are and where we’re from. As a result we can say that it defines a spatial matrix of the places we’re allowed to move to and from. This increased mobility of individuals around the world required a new form of control: the passport. As Mark B. Salter describesit as: “The passport is key artifact in the global mobility assemblage, understood as the dispositif of a population in circulation.”[2] But more importantly to the purpose of this discussion is how he refers to it being an example of the paradox outlined before: “It is a technology of freedom as well as a technology of control: not only does it afford a kind of freedom to travel internationally, but also it effects a kind on individualization.”[3] Even as the passport is a standardized form of identity verification available, open and understood by all, it also works to separate individuals and classify them into discrete groups.

Subsequently, this process of standardization has other series of ramifications, which contribute to intensify the degree of neurosis regarding our identities. In order to standardize ourindividual identities into a pool of similar characteristics that can be measured against other individuals’ characteristics, we are forced into adopting a new form of identity: one of neutrality. A passport photo never depicts an individual in its truest form. A passport photo has a series of guidelines that need to be met in order to classify as one and be a valid form of documentation. Salter describes this process of conforming to a “new you” as: “...the passport photograph creates a new ground for identification by the state: the presupposed isomorphism of the body to itself, the representation of the body to itself, the representation to the body, and the identity to both the body and the representation. It makes new kinds of authentication possible and creates the possibility that, for the first time, one cannot prove one’s own identity, because one’s body is not identical to its representations.”[4]

As a result, this can be thought as one of the first fissures in the process of identity validation through passports. The neutrality that we are bound to embrace in order to enter this realm of standardized identification, creates in turn another series of conflicts regarding gender, race and socio-economic backgrounds. Who gets to determine that this standardized form of identification is the optimal means to tell people apart from each other? Or is it another form of disguising the creation of more political and power boundaries between nations? Salter addresses this through the following: “Further, the failure of biometrics to successfully classify, and in particular to be efficient and effective at authenticating, vulnerable or marginalized populations is not an accidental outcome of the system but an inherent part of the system. The failure of biometric technologies is aleatory: it circulates in ways that reproduce other structures of power.”[5]

This problematic exists even without bringing the Internet of Things and Big Data into the conflict. When human passport controls are replaced by machines and their algorithms, these forms of standardization and neglect of certain populations are replicated at an exponential manner. An example of this would be the already implemented technology of AVATAR (Automated Virtual Assistant for Truth Assessments in Real Time). In spite of the fact that the use of this technology has allowed for a streamlining and ease of the passport control process, it hasn’t broken ground in expanding the horizons of identity validation beyond the neutrality of the passport photo. The unattainable image of the ideal citizen seems to prevail across gender, race and socio-political backgrounds, making it hard to truly revolutionize how we materialize our identity into a trustworthy representation. (“Biometric technologies ‘operate as systems for the discrimination of non-normative subjects, including people of colour, refugees and asylum seekers, transgender subjects, labourers and people with disabilities’.”[6]) This is clearly an issue in our current world with the growing refugee crisis and the increasing demand for global mobility and flexibility of labor as well as of goods and individuals.

A secondary fissure in the system of passports as a form of identity validation lies at its most basic level: the fact that as a document it intends to materialize trust. Boris Groys in his “In the Flow” essay approaches this from a different perspective where he explains that when we transitioned from analog to digital production, the digital copy opened an ease of replication that devalued the truthfulness of the original. If we think of this in parallel to what happens in how we represent and materialize our identities, we understand the inherent vulnerability that comes along with that act. Once it becomes a physical artifact it opens the possibilities to reproduction, forgery and ultimately, identity theft (“But once you materialize trust, you open up the possibility for replication or imitation. The passport becomes a research frontier: an ongoing experiment in the materialization of trust set against a ‘technological race’ between issuers, regulators, and forgers.”[7]). This now moves the discussion forward to the case studies I have selected as examples of companies which work in the market of identity security.

![]()

[8]

An unknown market to me before diving into this investigation, the world of biometrics is an up and coming source of innovation in the business world. A Google search for biometrics companies will yield hundreds of options of companies ranging in experience and size, reason why the ones I picked as particular case study examples are ones which deal with identity validation through different means. Initially the search was narrowed down to focusing on the companies bringing the most attention to the field as of last year. HYPR was named by Disruptor Daily amongst its top 10 Biometrics Companies to watch in 2017 [9]. HYPR is an example for decentralized authentication of identity, reliant on data encryption and almost a cloud software platform. On the other hand, Gemalto focuses on the material technology of

the physical product they offer their customers.

Both companies share an interesting marketing strategy to win over their customers’ trust through catchy slogans and the epitome of neutrality in their representation of individuals. Starting with HYPR, they sell themselves as being able to “TRUST ANYONE” and emphasizing the fact that “The Future is Decentralized.”

![]()

[10]

The eeriness of this image comes from the neutrality and almost lack of emotion depicted in the woman used as a face for the company. Similar to the blankness of a passport image, the dry expression on the woman’s face allows for them to project almost an idea of false security, where they have access to all your identity data. The “Trust Anyone” catch phrase works in both ways, customers are also trusting this type of companies to safe guard their individual information, believing that in no way these companies could possibly be also profiting from some kind of partnership with the government to provide them with more detailed information of their population. The key marketing factor this particular enterprise focuses on is mitigating the risk of identity theft by storing the individual’s information in a variety of places instead of one single location that can be more vulnerable to an attack (see diagrams below [11]).

![]()

Contrary to the premise of HYPR which operates majorly on synched data resources, Gemalto is an advocate for the physicality of the identity document and even the hardware used to validate a user’s ID. They market themselves as “Security to be free”, which immediately resonates with what was discussed earlier in the passport section with these documents being both a form of freedom and control. Moreover, upon closer inspection of their presentation, a phrase that caught my attention is the following becoming from one of its board members [12]:

![]()

What determines the strength of our identities? Our passport which establishes our citizenship and therefore rules out the places where we are allowed to go and not? Is it our racial background, socio-economic condition? I’d like to believe that this type of statement is geared more towards strengthening

the validity of our identities through the technologies used to represent them instead of any of the options previously outlined. Gemalto has a different workflow to the data heavy one of HYPR, where their process goes back and forth between physical identification and the use of data as a means of verifying that physical document [13]:

![]()

As much as Gemalto is trying to push forward the materialization of trust through their printing technologies and various layers of identity verification to deter fraud, they’re essentially not pushing the bar any higher in terms of truly innovating what we use to verify our identities. The clearest evidence for this is in the way they market their own products, which continue to establish a close connection to the neutral representation imposed by passports.

![]()

[14]

The image above in particular is loaded with the influence of the passport’s influence on the idea of an “ideal citizen”. It is understandable that they don’t show precisely what a particular country’s ID card would look like due to security reasons in order to avoid possible replication of the document, but their choice of location already conveys a sense of disruption between who we are and how we are portrayed in our identity documents. “Republic of Utopia” not only has a funny undertone to it, but it

further emphasizes the idea that for us to reach the levels of identity standardization set up to guarantee a successful validation platform, we must become almost a false representation of ourselves.

Perhaps, through the accuracy of 3D scanning we will be able to overcome the neurosis of the passport/ ID document photo matching the individual in real life. As architects we understand better than anyone the implications of collapsing three dimensions onto a planar representation, reason why it is comprehensible to see why a number of standards need to be established in the image used to represent a person’s facial features.

The intensification of our identity’s validation along with the neurosis that tags along with it, doesn’t seem to be nearing a stop in the near future. In fact, we are indeed living and moving towards an even more interconnected world, where we are the ones willing to provide this type of information without any prior request. The iPhone X’s Face ID is the first attempt at disguising this form of control through our dependency on smartphones and increasing need to interact with them in a faster, repeated and streamlined manner. On a skeptical reading of this technology, it is even interesting to see how Apple adds on the feature of Animoji as a fun, unsuspecting way of scanning our facial features and projecting them onto another character. We are closer than we may think to carry within our wallets a 3D scan of our faces that will serve as the ultimate key to unlock the physical barriers imposed to our movement through space and time controlled by nations.

Bibliography ↗

Yale School of Architecture

On a daily basis we seem to lose track of how many times we have to prove who we are to others in order to define how we move through space to carry out our many chores. Our identity defines our spatial realm without us even realizing it, or maybe we have grown so accustomed to verifying who we are that we don’t register the series of boundaries we cross hour by hour in an abstract way. Here is where my interest sprung for this investigation, where I intend to analyze the impact of Big Data on our real life and online identities. Some of the questions this paper seeks to answer are those related to the history and need for an identity and how through time there has been an intensification to have to prove who we are to have access to many of the services we require from day to day. More importantly, the paper includes a number of case studies of companies who have taken over the responsibility of assuring the veracity of their customers’ identities through data decentralization and material development as a form of biometrics. The fissures in the process of identification are what that draw our attention to how anxious our lives in the digital age have become in an ever growing neurotic quest to build a level of trust around who we are. At the same time, they become the gateways that compromise the security of how we interact with others’ identities.

As a preliminary exercise to the written version of this investigation, I underwent an identity use analysis on a common work day for me. The following is a graphic showing how many times throughout the day I had to make use of identity validation systems to carry forward basic, routine chores as a student at the Yale School of Architecture.

These illustrations bring to light how ubiquitous it is for us to verify our identities on almost an hourly basis. Each and every single one of these annotations is an abstraction of the traces left as a recognizable individual in a determined space and time. What they become are symbols for “Individual X was at Y at time Z and made use of the service A/ purchased item B, etc”. Our physicality is transformed into data that can be easily compiled and traced. In the era of Big Data and constant surveillance this becomes a resourceful pool of information for governments, where they don’t really have to make an effort to control their population in motion, we on our own provide them with this information.

They can also be thought of as a series of barriers that we are constantly crossing in order to get on with our lives and have access to the services we have grown used to. Another interpretation for which this type of graphic can be used for is to shed a light on our interaction or more even, dependency on our smartphones. When we put into numbers how many times we interact with our phones, it is eye-opening to see how much information about ourselves we’re currently feeding into these devices. This graphic record was carried out on a day after finals, where the turmoil of moving around the Architecture building was significantly less than usual and reflects on a lower use of login interfaces.

Personally, one of the most prominent discoveries for me was how Face ID has increased the ease of interaction with my phone, to the point where I find myself checking it more times than usual. The downside of this? I’m feeding more and more information about my facial characteristics to a device that can eventually improve its accuracy for facial recognition technologies used by corporations and governments. Overall, it would be interesting to carry forward this record over a week and represent it almost like a map with the locations of each of these identity interactions pinpointed to see how our identity allows us to move through space.

The concept of identity is already a slippery one without even taking Big Data into consideration. When we reflect upon how we even conceive the idea of identity, we realize that from the youngest of ages we always understand our identity as a game of representation and interpretation. Recognizing ourselves in the mirror is an interpretation of how we are represented by a reflective surface. There is no direct, empirical access to what our identity is, it is always conditioned through the medium of its representation: a photograph, a mirror, a passport, etc. Given the difficulty in defining identity truthfully, it is understandable why this becomes such a key element to our everyday lives. What does identity do for us? Why are we so concerned with guaranteeing its veracity and why do we have this constant need of distinguishing ourselves apart and then having to prove who we are to others?

In order to address these questions, it becomes necessary to first understand how we have recorded our individuality through time. The history of identity provides us with an understanding of how the degree of neuroticism regarding who we are has evolved throughout time. More importantly, this graphic timeline shows the growing technologies that spring out of the need of more layers of veracity added to the representation of who we are to others. [1]

First off, our identity exists within a paradox of freedom and control. Identity both provides us with the freedom to define who we are and how we want to be seen by others whilst simultaneously being a form of power and control for governments. Consequently, our identity establishes a trace that

connects who we are and where we’re from. As a result we can say that it defines a spatial matrix of the places we’re allowed to move to and from. This increased mobility of individuals around the world required a new form of control: the passport. As Mark B. Salter describesit as: “The passport is key artifact in the global mobility assemblage, understood as the dispositif of a population in circulation.”[2] But more importantly to the purpose of this discussion is how he refers to it being an example of the paradox outlined before: “It is a technology of freedom as well as a technology of control: not only does it afford a kind of freedom to travel internationally, but also it effects a kind on individualization.”[3] Even as the passport is a standardized form of identity verification available, open and understood by all, it also works to separate individuals and classify them into discrete groups.

Subsequently, this process of standardization has other series of ramifications, which contribute to intensify the degree of neurosis regarding our identities. In order to standardize ourindividual identities into a pool of similar characteristics that can be measured against other individuals’ characteristics, we are forced into adopting a new form of identity: one of neutrality. A passport photo never depicts an individual in its truest form. A passport photo has a series of guidelines that need to be met in order to classify as one and be a valid form of documentation. Salter describes this process of conforming to a “new you” as: “...the passport photograph creates a new ground for identification by the state: the presupposed isomorphism of the body to itself, the representation of the body to itself, the representation to the body, and the identity to both the body and the representation. It makes new kinds of authentication possible and creates the possibility that, for the first time, one cannot prove one’s own identity, because one’s body is not identical to its representations.”[4]

As a result, this can be thought as one of the first fissures in the process of identity validation through passports. The neutrality that we are bound to embrace in order to enter this realm of standardized identification, creates in turn another series of conflicts regarding gender, race and socio-economic backgrounds. Who gets to determine that this standardized form of identification is the optimal means to tell people apart from each other? Or is it another form of disguising the creation of more political and power boundaries between nations? Salter addresses this through the following: “Further, the failure of biometrics to successfully classify, and in particular to be efficient and effective at authenticating, vulnerable or marginalized populations is not an accidental outcome of the system but an inherent part of the system. The failure of biometric technologies is aleatory: it circulates in ways that reproduce other structures of power.”[5]

This problematic exists even without bringing the Internet of Things and Big Data into the conflict. When human passport controls are replaced by machines and their algorithms, these forms of standardization and neglect of certain populations are replicated at an exponential manner. An example of this would be the already implemented technology of AVATAR (Automated Virtual Assistant for Truth Assessments in Real Time). In spite of the fact that the use of this technology has allowed for a streamlining and ease of the passport control process, it hasn’t broken ground in expanding the horizons of identity validation beyond the neutrality of the passport photo. The unattainable image of the ideal citizen seems to prevail across gender, race and socio-political backgrounds, making it hard to truly revolutionize how we materialize our identity into a trustworthy representation. (“Biometric technologies ‘operate as systems for the discrimination of non-normative subjects, including people of colour, refugees and asylum seekers, transgender subjects, labourers and people with disabilities’.”[6]) This is clearly an issue in our current world with the growing refugee crisis and the increasing demand for global mobility and flexibility of labor as well as of goods and individuals.

A secondary fissure in the system of passports as a form of identity validation lies at its most basic level: the fact that as a document it intends to materialize trust. Boris Groys in his “In the Flow” essay approaches this from a different perspective where he explains that when we transitioned from analog to digital production, the digital copy opened an ease of replication that devalued the truthfulness of the original. If we think of this in parallel to what happens in how we represent and materialize our identities, we understand the inherent vulnerability that comes along with that act. Once it becomes a physical artifact it opens the possibilities to reproduction, forgery and ultimately, identity theft (“But once you materialize trust, you open up the possibility for replication or imitation. The passport becomes a research frontier: an ongoing experiment in the materialization of trust set against a ‘technological race’ between issuers, regulators, and forgers.”[7]). This now moves the discussion forward to the case studies I have selected as examples of companies which work in the market of identity security.

[8]

An unknown market to me before diving into this investigation, the world of biometrics is an up and coming source of innovation in the business world. A Google search for biometrics companies will yield hundreds of options of companies ranging in experience and size, reason why the ones I picked as particular case study examples are ones which deal with identity validation through different means. Initially the search was narrowed down to focusing on the companies bringing the most attention to the field as of last year. HYPR was named by Disruptor Daily amongst its top 10 Biometrics Companies to watch in 2017 [9]. HYPR is an example for decentralized authentication of identity, reliant on data encryption and almost a cloud software platform. On the other hand, Gemalto focuses on the material technology of

the physical product they offer their customers.

Both companies share an interesting marketing strategy to win over their customers’ trust through catchy slogans and the epitome of neutrality in their representation of individuals. Starting with HYPR, they sell themselves as being able to “TRUST ANYONE” and emphasizing the fact that “The Future is Decentralized.”

[10]

The eeriness of this image comes from the neutrality and almost lack of emotion depicted in the woman used as a face for the company. Similar to the blankness of a passport image, the dry expression on the woman’s face allows for them to project almost an idea of false security, where they have access to all your identity data. The “Trust Anyone” catch phrase works in both ways, customers are also trusting this type of companies to safe guard their individual information, believing that in no way these companies could possibly be also profiting from some kind of partnership with the government to provide them with more detailed information of their population. The key marketing factor this particular enterprise focuses on is mitigating the risk of identity theft by storing the individual’s information in a variety of places instead of one single location that can be more vulnerable to an attack (see diagrams below [11]).

Contrary to the premise of HYPR which operates majorly on synched data resources, Gemalto is an advocate for the physicality of the identity document and even the hardware used to validate a user’s ID. They market themselves as “Security to be free”, which immediately resonates with what was discussed earlier in the passport section with these documents being both a form of freedom and control. Moreover, upon closer inspection of their presentation, a phrase that caught my attention is the following becoming from one of its board members [12]:

What determines the strength of our identities? Our passport which establishes our citizenship and therefore rules out the places where we are allowed to go and not? Is it our racial background, socio-economic condition? I’d like to believe that this type of statement is geared more towards strengthening

the validity of our identities through the technologies used to represent them instead of any of the options previously outlined. Gemalto has a different workflow to the data heavy one of HYPR, where their process goes back and forth between physical identification and the use of data as a means of verifying that physical document [13]:

As much as Gemalto is trying to push forward the materialization of trust through their printing technologies and various layers of identity verification to deter fraud, they’re essentially not pushing the bar any higher in terms of truly innovating what we use to verify our identities. The clearest evidence for this is in the way they market their own products, which continue to establish a close connection to the neutral representation imposed by passports.

[14]

The image above in particular is loaded with the influence of the passport’s influence on the idea of an “ideal citizen”. It is understandable that they don’t show precisely what a particular country’s ID card would look like due to security reasons in order to avoid possible replication of the document, but their choice of location already conveys a sense of disruption between who we are and how we are portrayed in our identity documents. “Republic of Utopia” not only has a funny undertone to it, but it

further emphasizes the idea that for us to reach the levels of identity standardization set up to guarantee a successful validation platform, we must become almost a false representation of ourselves.

Perhaps, through the accuracy of 3D scanning we will be able to overcome the neurosis of the passport/ ID document photo matching the individual in real life. As architects we understand better than anyone the implications of collapsing three dimensions onto a planar representation, reason why it is comprehensible to see why a number of standards need to be established in the image used to represent a person’s facial features.

The intensification of our identity’s validation along with the neurosis that tags along with it, doesn’t seem to be nearing a stop in the near future. In fact, we are indeed living and moving towards an even more interconnected world, where we are the ones willing to provide this type of information without any prior request. The iPhone X’s Face ID is the first attempt at disguising this form of control through our dependency on smartphones and increasing need to interact with them in a faster, repeated and streamlined manner. On a skeptical reading of this technology, it is even interesting to see how Apple adds on the feature of Animoji as a fun, unsuspecting way of scanning our facial features and projecting them onto another character. We are closer than we may think to carry within our wallets a 3D scan of our faces that will serve as the ultimate key to unlock the physical barriers imposed to our movement through space and time controlled by nations.

Bibliography ↗

1. Graphic representation found at “Innovation in Identity”, Trulioo, accessed April 26th 2018, https://www.trulioo.com/blog/infographic-the-history-of-id-verification/

2. Mark B. Salter, Making Things International 1 Circuits and Motion, (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 18.

3. Mark B. Salter, Making Things International 1 Circuits and Motion, (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 14.

4. Mark B. Salter, Making Things International 1 Circuits and Motion, (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 22.

5. Mark B. Salter, Making Things International 1 Circuits and Motion, (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 30.

6. Mark B. Salter, Making Things International 1 Circuits and Motion, (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 54.

7. Mark B. Salter, Making Things International 1 Circuits and Motion, (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 14.

8. Graphic created by Vectorpocket at Freepik.com, accessed April 26th 2018, https://www.freepik.com/free-vector/set-of-vector-isometric-hacker-icons_1215904.htm#term=data%20security&page=1&position=22

9. Disruptor Daily website, Top 10 Biometrics Companies to Watch in 2017, accessed April 25th 2018, https://www.disruptordaily.com/top-10-biometrics-companies-2017/

10. HYPR website, accessed April 26th 2018, https://www.hypr.com/

11. Graphics taken from the downloadable brochure from HYPR website, accessed April 26th 2018, https://www.hypr.com/

12. Graphics taken from Gemalto website, accessed April 26th 2018, https://www.gemalto.com/companyinfo

13. Graphics taken from Gemalto Identity Programs downloadable brochure, accessed April 26th 2018, https://www.gemalto.com/govt/identity

14. Graphics taken from Gemalto Identity Programs downloadable brochure, accessed April 26th 2018, https://www.gemalto.com/govt/identity

2. Mark B. Salter, Making Things International 1 Circuits and Motion, (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 18.

3. Mark B. Salter, Making Things International 1 Circuits and Motion, (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 14.

4. Mark B. Salter, Making Things International 1 Circuits and Motion, (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 22.

5. Mark B. Salter, Making Things International 1 Circuits and Motion, (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 30.

6. Mark B. Salter, Making Things International 1 Circuits and Motion, (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 54.

7. Mark B. Salter, Making Things International 1 Circuits and Motion, (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 14.

8. Graphic created by Vectorpocket at Freepik.com, accessed April 26th 2018, https://www.freepik.com/free-vector/set-of-vector-isometric-hacker-icons_1215904.htm#term=data%20security&page=1&position=22

9. Disruptor Daily website, Top 10 Biometrics Companies to Watch in 2017, accessed April 25th 2018, https://www.disruptordaily.com/top-10-biometrics-companies-2017/

10. HYPR website, accessed April 26th 2018, https://www.hypr.com/

11. Graphics taken from the downloadable brochure from HYPR website, accessed April 26th 2018, https://www.hypr.com/

12. Graphics taken from Gemalto website, accessed April 26th 2018, https://www.gemalto.com/companyinfo

13. Graphics taken from Gemalto Identity Programs downloadable brochure, accessed April 26th 2018, https://www.gemalto.com/govt/identity

14. Graphics taken from Gemalto Identity Programs downloadable brochure, accessed April 26th 2018, https://www.gemalto.com/govt/identity