Dubai Logistics Infrastructure

Radhika Singh / 2018

Yale School of Architecture

Yale School of Architecture

In February 2006, the Government of Dubai issued a decree announcing

the creation of an independent authority for Jebel Ali Airport City, an AED

30 billion project that was (and still is) meant to become the world’s largest airport facility, with the capacity for 200 million passengers and 62 million

tons of cargo annually [1]. Once complete, the development complex would host several urban enclaves as sub-projects under its umbrella, including

Dubai Commercial City, Dubai Exhibition City, Residential City, and Dubai

Logistics City among others, in a single free economic zone. Covering an

area of 145 square kilometers, it will be the site of the World Expo 2020

and the biennial Dubai Airshow. Since then, the enterprise has undergone

several reformulations of scope and expected outcome - re-branded over the years as Al Maktoum International Airport, Dubai World Central,

and most recently, Dubai South [2], as well as revisions in both budget and

timelines for completion – yet remains a significant presence in mainstream

media and narratives of nation building in the United Arab Emirates.

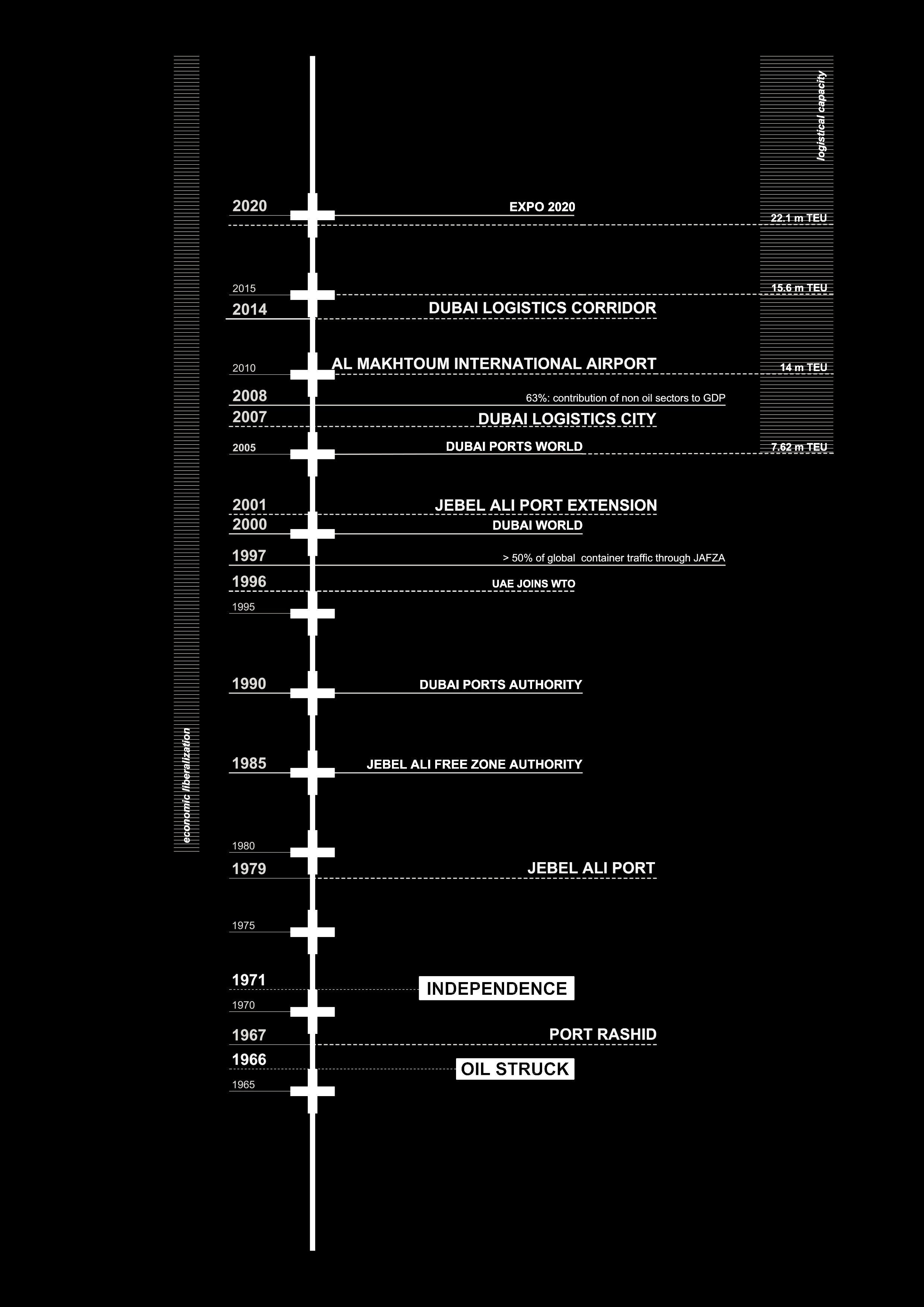

Ever laden with superlatives, undertakings like Dubai South are emblematic of contemporary development in the Persian Gulf, cloaked in boundless ambition and ostensibly unlimited resources that couple state policy readjustments with massive infrastructural projects to create new vehicles for industry. Using Dubai South and its connection to the free port of Jebel Ali via the Dubai Logistics Corridor as an example of this, this project examines the interdependence of logistical operations and the spatial and non-spatial infrastructure that supports it, as well as its territorial and geopolitical implications.

The Gulf has been at the forefront of rampant modernization over the last two decades, a “feverish production of urban substance, on sites where nomads roamed unmolested only half a century ago”[3]. While its initial growth was triggered by the discovery of oil, recent efforts to shift economy away from dependence on oil have led to ‘hyper-development’ and urban production that exemplifies “the repertoire of current urban prototypes”[4]. This might include typologies of the built environment such as communities, hotels, skyscrapers, and malls, but also the spatial products of international trade and commerce that manifest as free zones, warehouses, transportation infrastructure, and logistical clusters.

The UAE has been a member of the World Trade Organization since 1996 and has consistently been a proponent for stable trade relations with countries throughout the world. The country’s geographical coordinates at the crossroads of Europe and Asia position Dubai as an ideal location as a trade and logistics hub. In its current state, it is a landscape of vast means and aspiration, and any new development in the city is inextricably, and inevitably, linked to a larger network of global trends as opposed to any contextual roots. To this end, Dubai has worked to create a favourable business environment and economy open to foreign enterprise and invested heavily in the infrastructure needed to accommodate this. In recent years, Dubai has tried, perhaps successfully, to reposition itself as a platform capable of handling global logistical operations, advancing the developmental agenda for the entire region as it does so.

![]()

II.

This repositioning relies on a shift from dependence on the oil industry to the import and export of material to and from the region. Logistics operations entail the management and administration of international supply chains from production to distribution, and much of the logistical activity in the UAE occurs through the spaces of ports, free zones, and freight facilities: spaces that makeup the infrastructural matrix which services and facilitates this activity. Dubai’s efforts to advance its operational capabilities by frenetically assembling the infrastructure for logistics have made it a significant actor in the global freight network.

The logistical market of the UAE accounts for over $20 billion in revenues [5], to which freight forwarding contributes the largest share, followed by transportation, warehousing, and value added logistics services like packaging and cross-docking [6]. Dubai’s logistical sector benefits from a new phase in global trade, where the capacities to service and organize logistics are dominant success factors for buyer-supplier networks [7].

Once considered secondary to production, logistics are now a “key competitive advantage” in manufacturing. These systems span multiple dimensions: spatial/regional by way of storage and transportation, vertical flows in a supply chain of commodities from initial use of resources to manufacturing, and time taken for these exchanges to occur [8]. As physical manifestations, they have an impact on infrastructure development for logistics in terms of handling capacities, route delineation, frequency of services, and shipment networks.

The World Bank group uses a ‘Logistics Performance Index’ as a benchmarking tool “created to help countries identify the challenges and opportunities they face in their performance on trade logistics and what they can do to improve” this performance [9]. The index ranks economies based on ease of shipping and trade, determined by a global survey of operators – global freight forwarders and express carriers – who provide feedback on the logistics friendliness of the countries within which they operate.

As of the data available in 2018, the UAE ranks 13th on the global scale [10], the top performer among GCC countries. This ranking is in large part due to Dubai’s heavy investment in transportation nodes supplemented by a cluster of hundreds of logistics companies in the Jebel Ali Free Zone, or JAFZA, which is currently one of the world’s largest export hubs. Infrastructural development to handle ever more complex supply chains is a mainstay of Dubai’s Strategic Plan 2021 [11].

III.

This development is predicated on a network of elements within a global logistics space, comprising networked infrastructure, free trade zones, logistics hubs and trade corridors through which commodities circulate and transform before reaching consumers. The infrastructure of logistics is a critical endeavor of wider processes of commodities exchange and capital formation, linking “apparently disjunctive movements of accumulation across the urban scale.” [12] In a place like Dubai, infrastructure for logistics also has larger implications on sectors of real estate, trade, construction and retail. By becoming a means of urban production, it impacts urbanization patterns, capital accumulation and class formation. [13]

![]()

Dubai South is one such realization, encompassing the port of Jebel Ali, Jebel Ali Free Zone, and Al Maktoum International Airport. JAFZA is home to more than 400 companies engaged in the manufacturing, trade, logistics and service sectors – Logistics City covers an area of 200 square kilometers and, offering these companies substantial access to the free zone and port. The two largest regionally based logistics firms, Aramex and Agility, operate out of Dubai, with distribution centers in JAFZA. To present themselves as an ‘integrated logistics space’, the various infrastructural elements are part of one customs free zone with a high speed ‘logistics corridor’ that will radically reduce the time taken for goods to be transported from seaport to airport. These elements, both separately and together, make up the medium through which logistics operates.

Port:

In Dubai South, commodities are received, assembles, labeled, and repackaged for re-export. Maritime transport remains the primary mode of trade in the world economy, and JAFZA is a regional gateway to the Gulf. The Jebel Ali free port and the conglomerate that operates it, Dubai Ports World, facilitates over a hundred weekly services to 115 ports globally and services more than a hundred shipping lines. One of the largest man-made ports worldwide, it can accommodate ships of any size and offers a market for nearly 2 billion people.

Being integrated into an environment of ‘complete supply chain management, logistical networks, international sourcing of products and intermodalism’, changes the spatial relationships between ports like Jebel Ali and urban centers like Dubai. While ports were integrated into surrounding fabric historically, new mega ports exist as gated industrial complexes isolated from cities to allow for logistical capacities and connections to transportation nodes [14]. DP World exemplifies these trends and continues to expand with plans to increase its shipping handling capacity to 22.1 million TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units) by 2018.

Rail:

The UAE’s extensive road network is supplemented at present by a hundred kilometers of metro lines, with plans and projections for several additional rail projects – both national and regional. In 2009, member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council agreed to create a regional railway authority to oversee the development of a rail line that would link all six member states. The proposed $15 billion, 2177-kilometer GCC railway would “transform intra-regional transit and facilitate regional economic, not to mention socio-spatial integration.” [15] (It is noteworthy that “those who have been following the history of rail proposals in the Gulf have good reason to be skeptical. The same railway was a centerpiece of the 4th GCC summit in 1984” [16]). The GCC railway, however, is only one of many projects proposed or underway, marking a shift in climate for, and attitude towards rail infrastructure in the region that might be explained by the shift towards a logistically driven economy in the region. Trade among the Gulf countries was limited in the past due to similar, oil driven economies that translated into low incentives to develop inter-regional rail infrastructure, which changed in pursuit of foreign investment, diversifying trade patterns, and logistical capacities.

The Etihad Railway in the UAE is one such undertaking, a 1200 kilometer network connecting it with Oman and Saudi Arabia with dedicated freight lines planned to carry 50 million tons of goods per year. Etihad Rail has signed MoUs with several companies looking to use the railway to transport products and commodities, including ADNOC (Abu Dhabi National Oil Company), Arkan, Emirates Steel, Al Dahra Agriculture Company, and Etisalat, and, of course, DP World. [17]

This network is seeking to “effectively integrate” the railway with key ports and industrial zones, including Dubai South and Jebel Ali Port, to “enable the more efficient transfer of containerized freight arriving at the port to bring benefits to logistics companies and the UAE economy as a whole”. [18]

Road:

The road network across the Arabian Peninsula spans almost 170,000 kilometers, and Dubai South enjoys connectivity by road across the Gulf within a period of three days. The UAE’s Ministry of Infrastructure Development announced plans in 2017 to develop a network of roads to link the Expo 2020 site in Dubai South with the mainland downtowns and allow goods from port to be distributed with ease throughout the Emirate.

![]()

Dedicated Corridor–Land, Air, Sea:

The master plan for Dubai Logistics City, first made public in 2006, was limited to the confines of Dubai South, but has since been revised to incorporate the JAFZA and Jebel Ali Port/ DP World through what is being called the Dubai Logistics Corridor. Made possible through the collaboration between JAFZA and Dubai Aviation City Corporation, the mainstay of this corridor is a highway that connects the Al Maktoum International Airport in Dubai South with the port, creating a sealand-air link. Being called the first and only “integrated sea-air corridor”, as a companion to Dubai South, the DLC will radically reduce the time taken for the transfer of goods from sea to air via overland rail and road links. The stream of logistical flows position Dubai Logistics Corridor as a ‘trimodal’ option now, and with the anticipated completion of the Etihad Rail, a ‘quadra-modal’ system in the future. It is already, however, one of the largest multi-modal logistics platforms in the world.

With these changes anticipated in the transportation networks, including the GCC railway network with dedicated freight lines, as well as the road networks across the Emirates improvements in efficiency in logistical activities are expected. [19] The integration of transport modes and standardization of procedures might boost economies of scale, [20] still increasing Dubai’s role as a critical node in the global supply chain. Intermodal links need to be upgraded/ regulated within the Emirates.

With 38 free zones geographically close to each other across the country, [21] co-location such as that in Dubai South and interlinks between these zones catalyzing business growth, the locations of Dubai’s free zones in turn enhances the efficiency of urban freight transport systems.

IV.

Logistical infrastructure also affects, and is impacted by, non-spatial and regulatory frameworks. The performance of this constellation of exchange infrastructure hinges on institutional and organizational constructs for the practices adopted for shipping and handling. It plays a critical role in decreasing circulation time and framing circulatory space – goods manufactured in Asian countries are distributed through Dubai to Africa, the Middle East, the Russian Commonwealth, and Europe in two weeks of transit time. In a coupling of spatial and procedural strategies, the Dubai Logistics Corridor relaxes customs and legal compliance procedures within its confines, allowing products traveling within DP World, JAFZA and Dubai South (sea-land-air cargo) to go through customs only once at their first point of entry, after which travel within the corridor is free if shipments comply with regulations. This lubrication of space for logistical activity is most cost effective and collapses space/ time considerations considerably: the time taken to unload shipments at Jebel Ali Port, clear containers and transport goods to Al Maktoum International Airport is reduced from 2 to 3 days to only 4 hours, exemplifying trade elasticities afforded to goods globally. [22]

Other administrative systems with considerations of time to ensure a continuous flow of goods involve the availability of these services around the clock, further reducing the lead times needed to clear merchandise for logistics companies that continue to increase their shipment capacities and warehousing capabilities. The transportation of goods over land is restricted by peak traffic hours – current regulations prevent trucks over 2.5 tons from using major urban thoroughfares at certain times of day. The Dubai Logistics Corridor addresses this by providing dedicated freight space from port to air.

The DLC is also a unified virtual space, connected by an online portal called Dubai Trade, that allows businesses to submit import or export regulatory documents to multiple state agencies online, blurring the boundaries between physical and technological networks. In the words of Mohsen Ahmad, Vice President of Dubai South’s Logistics District, in March 2015:

“The Logistics District became the first free zone in Dubai to invest in an electronic system that regulates the process of issuing entry permits. Implemented with Dubai Customs, the system is in line with DWC’s commitment to applying smart solutions across all of its districts, corresponding to the Dubai government’s strategy to transform the Emirate into a smart city.” [23]

Financial infrastructure supplements the strategies outlined by Ahmed, that have markedly improved the UAE’s rankings on the Logistical Performance Index. In recent years, the country has provided businesses with several incentives and reduced the cost of setting up operations by removing minimum capital requirements, liberalizing visa policies, making available maritime legal expertise and insurance, and exempting tax on all imports and exports. [24] Each free zone is governed by its own Free Zone Authority and mandated business polities of state government.

![]()

V.

The alarming ease with which logistical operations have been allowed to transcend geopolitical, financial and economic considerations lends itself to an attribution of the qualities of the Dubai Logistics Corridor to neoliberal paradigms of global trade. Clearer, however, are the impacts of logistical infrastructure on “urbanization patterns, capital accumulation and class formation” in Dubai, and cities on the Arabian Peninsula. Trade infrastructure plays a preeminent role in the production of Dubai’s economic geography as a sea-air trading hub, which in turn is largely dependent on the elementary units that comprise commodities exchanges.

Dubai is entering and creating a new economic geography where infrastructure and logistics with institutional trade facilities multiply opportunities for trade and provide international connectedness for a region that was once on the periphery of global supply chains, where transport infrastructure plays an essential role in linking diverse movements of capital accumulation in Dubai. [25]

This means of citmaking is increasingly seen as an aspirational model being replicated internationally (the concept of a logistics city was a “Dubai innovation” [26])- Dubai Logistics City sets “momentous precedents for the production of urban space and the politics of infrastructure protection reaching far beyond Dubai and the Gulf Region.”[27] The larger territorial implications of this also manifest as Dubai Ports and related conglomerates have expanded their interests overseas through public private partnerships and acquisitions. DP world, starting to dominate markets internationally, holds global assets in a network of more than 80 marine and inland terminals in 6 continents.

The relationships between Dubai’s logistics/ transport infrastructure and its geopolitical positioning are also noteworthy: the control of all the port land lies in the hands of the ruler of Dubai, who provides freehold to Dubai Port Authority. All agencies involved work in tandem with state owned holding corporations. Perhaps one of the most challenging aspects of understanding the network of actors involved in these enterprises is the constant restructuring and reformulations of organizational entities and alliances, particularly given the interplay between what is eminently governmental in organizational structure, while the infrastructural fixtures themselves are weighed on their performance as destinations for international investments of capital.

The focus on logistical capacities inserts Dubai into global networks of trade, where spaces like Dubai South become nodes in a complex logistics space where the only goal appears to be enhanced efficiency in facilitating movement of goods. Infrastructure is at the core of its particular brand of capitalism and urban development, both of which might skirt usual forms of analysis due to the myriad, overlapping connections between actors, stakeholders, networks of infrastructure and ecologies at urban, national, and global scales.

Ever laden with superlatives, undertakings like Dubai South are emblematic of contemporary development in the Persian Gulf, cloaked in boundless ambition and ostensibly unlimited resources that couple state policy readjustments with massive infrastructural projects to create new vehicles for industry. Using Dubai South and its connection to the free port of Jebel Ali via the Dubai Logistics Corridor as an example of this, this project examines the interdependence of logistical operations and the spatial and non-spatial infrastructure that supports it, as well as its territorial and geopolitical implications.

The Gulf has been at the forefront of rampant modernization over the last two decades, a “feverish production of urban substance, on sites where nomads roamed unmolested only half a century ago”[3]. While its initial growth was triggered by the discovery of oil, recent efforts to shift economy away from dependence on oil have led to ‘hyper-development’ and urban production that exemplifies “the repertoire of current urban prototypes”[4]. This might include typologies of the built environment such as communities, hotels, skyscrapers, and malls, but also the spatial products of international trade and commerce that manifest as free zones, warehouses, transportation infrastructure, and logistical clusters.

The UAE has been a member of the World Trade Organization since 1996 and has consistently been a proponent for stable trade relations with countries throughout the world. The country’s geographical coordinates at the crossroads of Europe and Asia position Dubai as an ideal location as a trade and logistics hub. In its current state, it is a landscape of vast means and aspiration, and any new development in the city is inextricably, and inevitably, linked to a larger network of global trends as opposed to any contextual roots. To this end, Dubai has worked to create a favourable business environment and economy open to foreign enterprise and invested heavily in the infrastructure needed to accommodate this. In recent years, Dubai has tried, perhaps successfully, to reposition itself as a platform capable of handling global logistical operations, advancing the developmental agenda for the entire region as it does so.

II.

This repositioning relies on a shift from dependence on the oil industry to the import and export of material to and from the region. Logistics operations entail the management and administration of international supply chains from production to distribution, and much of the logistical activity in the UAE occurs through the spaces of ports, free zones, and freight facilities: spaces that makeup the infrastructural matrix which services and facilitates this activity. Dubai’s efforts to advance its operational capabilities by frenetically assembling the infrastructure for logistics have made it a significant actor in the global freight network.

The logistical market of the UAE accounts for over $20 billion in revenues [5], to which freight forwarding contributes the largest share, followed by transportation, warehousing, and value added logistics services like packaging and cross-docking [6]. Dubai’s logistical sector benefits from a new phase in global trade, where the capacities to service and organize logistics are dominant success factors for buyer-supplier networks [7].

Once considered secondary to production, logistics are now a “key competitive advantage” in manufacturing. These systems span multiple dimensions: spatial/regional by way of storage and transportation, vertical flows in a supply chain of commodities from initial use of resources to manufacturing, and time taken for these exchanges to occur [8]. As physical manifestations, they have an impact on infrastructure development for logistics in terms of handling capacities, route delineation, frequency of services, and shipment networks.

The World Bank group uses a ‘Logistics Performance Index’ as a benchmarking tool “created to help countries identify the challenges and opportunities they face in their performance on trade logistics and what they can do to improve” this performance [9]. The index ranks economies based on ease of shipping and trade, determined by a global survey of operators – global freight forwarders and express carriers – who provide feedback on the logistics friendliness of the countries within which they operate.

As of the data available in 2018, the UAE ranks 13th on the global scale [10], the top performer among GCC countries. This ranking is in large part due to Dubai’s heavy investment in transportation nodes supplemented by a cluster of hundreds of logistics companies in the Jebel Ali Free Zone, or JAFZA, which is currently one of the world’s largest export hubs. Infrastructural development to handle ever more complex supply chains is a mainstay of Dubai’s Strategic Plan 2021 [11].

III.

This development is predicated on a network of elements within a global logistics space, comprising networked infrastructure, free trade zones, logistics hubs and trade corridors through which commodities circulate and transform before reaching consumers. The infrastructure of logistics is a critical endeavor of wider processes of commodities exchange and capital formation, linking “apparently disjunctive movements of accumulation across the urban scale.” [12] In a place like Dubai, infrastructure for logistics also has larger implications on sectors of real estate, trade, construction and retail. By becoming a means of urban production, it impacts urbanization patterns, capital accumulation and class formation. [13]

Dubai South is one such realization, encompassing the port of Jebel Ali, Jebel Ali Free Zone, and Al Maktoum International Airport. JAFZA is home to more than 400 companies engaged in the manufacturing, trade, logistics and service sectors – Logistics City covers an area of 200 square kilometers and, offering these companies substantial access to the free zone and port. The two largest regionally based logistics firms, Aramex and Agility, operate out of Dubai, with distribution centers in JAFZA. To present themselves as an ‘integrated logistics space’, the various infrastructural elements are part of one customs free zone with a high speed ‘logistics corridor’ that will radically reduce the time taken for goods to be transported from seaport to airport. These elements, both separately and together, make up the medium through which logistics operates.

Port:

In Dubai South, commodities are received, assembles, labeled, and repackaged for re-export. Maritime transport remains the primary mode of trade in the world economy, and JAFZA is a regional gateway to the Gulf. The Jebel Ali free port and the conglomerate that operates it, Dubai Ports World, facilitates over a hundred weekly services to 115 ports globally and services more than a hundred shipping lines. One of the largest man-made ports worldwide, it can accommodate ships of any size and offers a market for nearly 2 billion people.

Being integrated into an environment of ‘complete supply chain management, logistical networks, international sourcing of products and intermodalism’, changes the spatial relationships between ports like Jebel Ali and urban centers like Dubai. While ports were integrated into surrounding fabric historically, new mega ports exist as gated industrial complexes isolated from cities to allow for logistical capacities and connections to transportation nodes [14]. DP World exemplifies these trends and continues to expand with plans to increase its shipping handling capacity to 22.1 million TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units) by 2018.

Rail:

The UAE’s extensive road network is supplemented at present by a hundred kilometers of metro lines, with plans and projections for several additional rail projects – both national and regional. In 2009, member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council agreed to create a regional railway authority to oversee the development of a rail line that would link all six member states. The proposed $15 billion, 2177-kilometer GCC railway would “transform intra-regional transit and facilitate regional economic, not to mention socio-spatial integration.” [15] (It is noteworthy that “those who have been following the history of rail proposals in the Gulf have good reason to be skeptical. The same railway was a centerpiece of the 4th GCC summit in 1984” [16]). The GCC railway, however, is only one of many projects proposed or underway, marking a shift in climate for, and attitude towards rail infrastructure in the region that might be explained by the shift towards a logistically driven economy in the region. Trade among the Gulf countries was limited in the past due to similar, oil driven economies that translated into low incentives to develop inter-regional rail infrastructure, which changed in pursuit of foreign investment, diversifying trade patterns, and logistical capacities.

The Etihad Railway in the UAE is one such undertaking, a 1200 kilometer network connecting it with Oman and Saudi Arabia with dedicated freight lines planned to carry 50 million tons of goods per year. Etihad Rail has signed MoUs with several companies looking to use the railway to transport products and commodities, including ADNOC (Abu Dhabi National Oil Company), Arkan, Emirates Steel, Al Dahra Agriculture Company, and Etisalat, and, of course, DP World. [17]

This network is seeking to “effectively integrate” the railway with key ports and industrial zones, including Dubai South and Jebel Ali Port, to “enable the more efficient transfer of containerized freight arriving at the port to bring benefits to logistics companies and the UAE economy as a whole”. [18]

Road:

The road network across the Arabian Peninsula spans almost 170,000 kilometers, and Dubai South enjoys connectivity by road across the Gulf within a period of three days. The UAE’s Ministry of Infrastructure Development announced plans in 2017 to develop a network of roads to link the Expo 2020 site in Dubai South with the mainland downtowns and allow goods from port to be distributed with ease throughout the Emirate.

Dedicated Corridor–Land, Air, Sea:

The master plan for Dubai Logistics City, first made public in 2006, was limited to the confines of Dubai South, but has since been revised to incorporate the JAFZA and Jebel Ali Port/ DP World through what is being called the Dubai Logistics Corridor. Made possible through the collaboration between JAFZA and Dubai Aviation City Corporation, the mainstay of this corridor is a highway that connects the Al Maktoum International Airport in Dubai South with the port, creating a sealand-air link. Being called the first and only “integrated sea-air corridor”, as a companion to Dubai South, the DLC will radically reduce the time taken for the transfer of goods from sea to air via overland rail and road links. The stream of logistical flows position Dubai Logistics Corridor as a ‘trimodal’ option now, and with the anticipated completion of the Etihad Rail, a ‘quadra-modal’ system in the future. It is already, however, one of the largest multi-modal logistics platforms in the world.

With these changes anticipated in the transportation networks, including the GCC railway network with dedicated freight lines, as well as the road networks across the Emirates improvements in efficiency in logistical activities are expected. [19] The integration of transport modes and standardization of procedures might boost economies of scale, [20] still increasing Dubai’s role as a critical node in the global supply chain. Intermodal links need to be upgraded/ regulated within the Emirates.

With 38 free zones geographically close to each other across the country, [21] co-location such as that in Dubai South and interlinks between these zones catalyzing business growth, the locations of Dubai’s free zones in turn enhances the efficiency of urban freight transport systems.

IV.

Logistical infrastructure also affects, and is impacted by, non-spatial and regulatory frameworks. The performance of this constellation of exchange infrastructure hinges on institutional and organizational constructs for the practices adopted for shipping and handling. It plays a critical role in decreasing circulation time and framing circulatory space – goods manufactured in Asian countries are distributed through Dubai to Africa, the Middle East, the Russian Commonwealth, and Europe in two weeks of transit time. In a coupling of spatial and procedural strategies, the Dubai Logistics Corridor relaxes customs and legal compliance procedures within its confines, allowing products traveling within DP World, JAFZA and Dubai South (sea-land-air cargo) to go through customs only once at their first point of entry, after which travel within the corridor is free if shipments comply with regulations. This lubrication of space for logistical activity is most cost effective and collapses space/ time considerations considerably: the time taken to unload shipments at Jebel Ali Port, clear containers and transport goods to Al Maktoum International Airport is reduced from 2 to 3 days to only 4 hours, exemplifying trade elasticities afforded to goods globally. [22]

Other administrative systems with considerations of time to ensure a continuous flow of goods involve the availability of these services around the clock, further reducing the lead times needed to clear merchandise for logistics companies that continue to increase their shipment capacities and warehousing capabilities. The transportation of goods over land is restricted by peak traffic hours – current regulations prevent trucks over 2.5 tons from using major urban thoroughfares at certain times of day. The Dubai Logistics Corridor addresses this by providing dedicated freight space from port to air.

The DLC is also a unified virtual space, connected by an online portal called Dubai Trade, that allows businesses to submit import or export regulatory documents to multiple state agencies online, blurring the boundaries between physical and technological networks. In the words of Mohsen Ahmad, Vice President of Dubai South’s Logistics District, in March 2015:

“The Logistics District became the first free zone in Dubai to invest in an electronic system that regulates the process of issuing entry permits. Implemented with Dubai Customs, the system is in line with DWC’s commitment to applying smart solutions across all of its districts, corresponding to the Dubai government’s strategy to transform the Emirate into a smart city.” [23]

Financial infrastructure supplements the strategies outlined by Ahmed, that have markedly improved the UAE’s rankings on the Logistical Performance Index. In recent years, the country has provided businesses with several incentives and reduced the cost of setting up operations by removing minimum capital requirements, liberalizing visa policies, making available maritime legal expertise and insurance, and exempting tax on all imports and exports. [24] Each free zone is governed by its own Free Zone Authority and mandated business polities of state government.

V.

The alarming ease with which logistical operations have been allowed to transcend geopolitical, financial and economic considerations lends itself to an attribution of the qualities of the Dubai Logistics Corridor to neoliberal paradigms of global trade. Clearer, however, are the impacts of logistical infrastructure on “urbanization patterns, capital accumulation and class formation” in Dubai, and cities on the Arabian Peninsula. Trade infrastructure plays a preeminent role in the production of Dubai’s economic geography as a sea-air trading hub, which in turn is largely dependent on the elementary units that comprise commodities exchanges.

Dubai is entering and creating a new economic geography where infrastructure and logistics with institutional trade facilities multiply opportunities for trade and provide international connectedness for a region that was once on the periphery of global supply chains, where transport infrastructure plays an essential role in linking diverse movements of capital accumulation in Dubai. [25]

This means of citmaking is increasingly seen as an aspirational model being replicated internationally (the concept of a logistics city was a “Dubai innovation” [26])- Dubai Logistics City sets “momentous precedents for the production of urban space and the politics of infrastructure protection reaching far beyond Dubai and the Gulf Region.”[27] The larger territorial implications of this also manifest as Dubai Ports and related conglomerates have expanded their interests overseas through public private partnerships and acquisitions. DP world, starting to dominate markets internationally, holds global assets in a network of more than 80 marine and inland terminals in 6 continents.

The relationships between Dubai’s logistics/ transport infrastructure and its geopolitical positioning are also noteworthy: the control of all the port land lies in the hands of the ruler of Dubai, who provides freehold to Dubai Port Authority. All agencies involved work in tandem with state owned holding corporations. Perhaps one of the most challenging aspects of understanding the network of actors involved in these enterprises is the constant restructuring and reformulations of organizational entities and alliances, particularly given the interplay between what is eminently governmental in organizational structure, while the infrastructural fixtures themselves are weighed on their performance as destinations for international investments of capital.

The focus on logistical capacities inserts Dubai into global networks of trade, where spaces like Dubai South become nodes in a complex logistics space where the only goal appears to be enhanced efficiency in facilitating movement of goods. Infrastructure is at the core of its particular brand of capitalism and urban development, both of which might skirt usual forms of analysis due to the myriad, overlapping connections between actors, stakeholders, networks of infrastructure and ecologies at urban, national, and global scales.

1. Saifur Raman, “Decree on Jebel Ali Airport City Soon”, Gulf News, February 16, 2006. https://gulfnews.com/business/aviation/decree-on-jebel-ali-airport-city-soon-1.225376

2. The National Staff, ‘Dubai World Central renamed ‘Dubai South’’, The National, August 19, 2015. https://www.thenational. ae/business/dubai-world-central-renamed-dubai-south-1.72015

3. Rem Koolhaas, Al Manakh. Netherlands: Stichting Archis, 2007

4. Ibid.

5. Balan Sundarkani, “Transforming Dubai Logistics Corridor into a Global Logistics Hub”, Asian Journal of Management Cases 14 (2), 2017: 115-136

6. Ibid.

7. Nasser Saidi, Aathira Prasad, Fabio Scacciavillani, Tommaso Roi,”Dubai World Central and the Evolution of Dubai Logistic Cluster”, Economic Note No. 10, August 2010

8. Ibid.

9. World Bank Logistics Performance Index, accessed May 08, 2018, https://lpi.worldbank.org

10. World Bank Logistics Performance Index. Global Rankings, accessed May 08, 2018, https://lpi.worldbank.org/ international/global

11. DP2021 Booklet, Government of Dubai, accessed May 10, 2018, https://www.dubaiplan2021.ae

12. Rafeef Ziadah, “Transport Infrastructure and Logistics in the Making of Dubai Inc.”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 42 Number 2, March 2018: 182-197

13. Ibid.

14. Rafeef Ziadah, “Transport Infrastructure and Logistics in the Making of Dubai Inc.”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 42 Number 2, March 2018: 182-197

15. Tabitha Decker, “Express Integration: The Return of the GCC Rail Project”, in Al Manakh 2: Gulf Continued, ed. by Todd Reisz, Archis 2010. 278-279

16. Ibid.

17. UAE Vision 2021, Etihad Rail, accessed on May 12, 2018, https://www.etihadrail.ae

18. Etihad Railway Factsheet, accessed May 12, 2018, https://www.etihadrail.ae/sites/default/files/pdf/factsheets.pdf

19. Balan Sundarkani, “Transforming Dubai Logistics Corridor into a Global Logistics Hub”, Asian Journal of Management Cases 14 (2), 2017: 115-136

20. Nasser Saidi, Aathira Prasad, Fabio Scacciavillani, Tommaso Roi,”Dubai World Central and the Evolution of Dubai Logistic Cluster”, Economic Note No. 10, August 2010r

21. UAE Freezone Registration portal, accessed May 13, 2018, http://freezoneregistration.ae/

22. Nasser Saidi, Aathira Prasad, Fabio Scacciavillani, Tommaso Roi,”Dubai World Central and the Evolution of Dubai Logistic Cluster”, Economic Note No. 10, August 2010

23. Balan Sundarkani, “Transforming Dubai Logistics Corridor into a Global Logistics Hub”, Asian Journal of Management Cases 14 (2), 2017: 115-136.

24. Rafeef Ziadah, “Transport Infrastructure and Logistics in the Making of Dubai Inc.”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 42 Number 2, March 2018: 182-197

25. Rafeef Ziadah, “Transport Infrastructure and Logistics in the Making of Dubai Inc.”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 42 Number 2, March 2018: 182-197

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.

2. The National Staff, ‘Dubai World Central renamed ‘Dubai South’’, The National, August 19, 2015. https://www.thenational. ae/business/dubai-world-central-renamed-dubai-south-1.72015

3. Rem Koolhaas, Al Manakh. Netherlands: Stichting Archis, 2007

4. Ibid.

5. Balan Sundarkani, “Transforming Dubai Logistics Corridor into a Global Logistics Hub”, Asian Journal of Management Cases 14 (2), 2017: 115-136

6. Ibid.

7. Nasser Saidi, Aathira Prasad, Fabio Scacciavillani, Tommaso Roi,”Dubai World Central and the Evolution of Dubai Logistic Cluster”, Economic Note No. 10, August 2010

8. Ibid.

9. World Bank Logistics Performance Index, accessed May 08, 2018, https://lpi.worldbank.org

10. World Bank Logistics Performance Index. Global Rankings, accessed May 08, 2018, https://lpi.worldbank.org/ international/global

11. DP2021 Booklet, Government of Dubai, accessed May 10, 2018, https://www.dubaiplan2021.ae

12. Rafeef Ziadah, “Transport Infrastructure and Logistics in the Making of Dubai Inc.”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 42 Number 2, March 2018: 182-197

13. Ibid.

14. Rafeef Ziadah, “Transport Infrastructure and Logistics in the Making of Dubai Inc.”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 42 Number 2, March 2018: 182-197

15. Tabitha Decker, “Express Integration: The Return of the GCC Rail Project”, in Al Manakh 2: Gulf Continued, ed. by Todd Reisz, Archis 2010. 278-279

16. Ibid.

17. UAE Vision 2021, Etihad Rail, accessed on May 12, 2018, https://www.etihadrail.ae

18. Etihad Railway Factsheet, accessed May 12, 2018, https://www.etihadrail.ae/sites/default/files/pdf/factsheets.pdf

19. Balan Sundarkani, “Transforming Dubai Logistics Corridor into a Global Logistics Hub”, Asian Journal of Management Cases 14 (2), 2017: 115-136

20. Nasser Saidi, Aathira Prasad, Fabio Scacciavillani, Tommaso Roi,”Dubai World Central and the Evolution of Dubai Logistic Cluster”, Economic Note No. 10, August 2010r

21. UAE Freezone Registration portal, accessed May 13, 2018, http://freezoneregistration.ae/

22. Nasser Saidi, Aathira Prasad, Fabio Scacciavillani, Tommaso Roi,”Dubai World Central and the Evolution of Dubai Logistic Cluster”, Economic Note No. 10, August 2010

23. Balan Sundarkani, “Transforming Dubai Logistics Corridor into a Global Logistics Hub”, Asian Journal of Management Cases 14 (2), 2017: 115-136.

24. Rafeef Ziadah, “Transport Infrastructure and Logistics in the Making of Dubai Inc.”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 42 Number 2, March 2018: 182-197

25. Rafeef Ziadah, “Transport Infrastructure and Logistics in the Making of Dubai Inc.”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 42 Number 2, March 2018: 182-197

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.